The fieldwork of the second season of the Ghazali Archaeological Site Presentation project started on the 7th of January 2014.

CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION

The priority of this season was to begin works aimed at the preservation of the monastery. The following procedures have been carried out in regard to the main church of the monastery:

Documentation

Tracing of the graffiti; photographic documentation of the state of preservation and the work in progress has been done.

Cleaning

Layers of mud and dust were cleaned using clean water, soft sponges, and brushes. In case of the intensive filth 2% Contrad 2000 for the regular dirt and 20% Ammonium Carbonate solution in water for salt or gypsum recrystallization. 30% Ethanol solution or pure Ethanol and Acetone were used.

Consolidation of the plaster

The consolidation of the plaster has been achieved in three different ways depending on the state of degradation. After cleaning, the first step for the weak surfaces was the impregnation with lime water by the use of sprayers or brushes. Some of the borders needed consolidation with 10% Primal AC-33 solution in water and ethanol. The edges were soaked with a 30% ethanol solution in water before the consolidation, to facilitate the penetration of the resin. The powdery mortar was consolidated with a 5% solution of Lime Casein in water anticipated by the use of 30% Ethanol solution. This process was repeated several times according to the disintegration of the mortar.

Filling of gaps and voids

Empty spaces between the layer of plaster and the construction support were consolidated by injections of Primal AC-33 (1:5 in water), Ledan TB1 (1:2 with water), or with liquid lime mortar. The result was satisfactory. The detached edges and some gaps were filled by a lime mortar modified by white cement. Two recipes were used depending on the characteristic of the original material:

Slaked lime, white cement, sand (1:1:4)

Slaked lime, white cement, calcium carbonate, sand (1:1:1:4)

Consolidation of the paint layer and whitewashes

The powdery whitewashes were consolidated with lime water, with the addition of 30% Ethanol solution. Flaking or powdered paint layer was consolidated with a 5% Ammonium Casein solution.

The conservation work done in this season was very basic but extensive and was focused on the consolidation of the fragile plaster of the walls of the church containing the graffito’s, traces of the paint layer and the benches around the building. The result of the work was good, but for full protection some extra measures are needed. The top of the walls should be partially reconstructed and sealed by a waterproof mortar and spaces between stones should be filled as well. The floor of the church needs urgent intervention as tiles are loose and some stones are in a very bad state.

During the season the surface of the walls over 200 square meters size has been cleaned, stuck back to the construction of the wall and a protective band had been made all over the edges of preserved plaster. Apart from that all of the inscriptions and drawings have been traced on foil before and after the conservation. Preliminary results of the conservation will be published in Der Antike Sudan in 2014, and in the first volume on the monastery of Ghazali which is set to be published at the end of 2015 or early 2016. The conservation also revealed some previously unknown parts of the decoration of the church.

In regard to the protection of the monument: some pathways were blocked with stone walls to change the tourist routes in order to limit further damage to the building. Other fragile places were covered with clean sand.

PRELIMINARY REPORT OF THE FIELD SEASON WINTER 2014

Dr. Artur Obłuski,

The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELDWORK

The aim of archaeological works this season was to continue excavations of the worst preserved part of the monastery, clearing the site from the debris and several piles of stones set up during the excavations in the 1950ies in order to complement the plan of the site. Due to the limited financial support, the 2014 season works focused on cleaning of the eastern part of the monastery and the surrounding area of the church in order to facilitate the conservation works. The area of approximately 400 sq. m. has been excavated.

In the eastern part of the cemetery, a row of toilets running all along the outer wall of the monastery was found. They were organized in groups of three, parted by a corridor leading to a cloak channel running between the toilets and the outer wall of the monastery. The toilets are dated to at least two separate phases of occupation of the monastery. Two groups located in the area adjacent to the central part of the eastern wall predate the group located east of the church. Unlike the central group of toilets, they were built directly over the cloak channel.

In the second area of excavation north of the Northern Church, a set of 7 rooms built of sun-dried brick was uncovered. The orientation of the rooms is on the axis of the buildings in the northern part of the monastery. They are poorly preserved, no higher than 0.75 m above the floor level. They are inter-communicated and bear evidence of at least two phases of construction and occupation. One of the rooms was paved with pottery tiles.

CEMETERY 2

Two of several dozen grave structures, clearly visible on the surface, were selected for excavation. The layers of soil and rubble of decayed stone covering them were removed exposing them to the level they had originally been built on. They were photographed and measured. The larger superstructure had been thoroughly documented and disassembled and the underlying grave pit was explored.

At the very bottom of the pit, a skeleton of a male aged 50 (or more) has been discovered. The burial was undisturbed, and the skeleton was found laying in anatomical position. Lying in a supine position along the East-West axis, with head to the West, following the widely recognized pattern of Nubian Christian burials. The head of the interred was protected by a head shelter of three mud bricks forming a roof above it. The moisture, fungi, and plant roots have damaged the bones considerably leaving them very fragile and fracture prone, making their proper recovery very difficult. The inhumation was documented in detail and excavated.

As expected, no grave goods have been found accompanying the body, save some small fragments of a shroud or clothing, heavily decayed. Those have been sampled for further examinations to be carried out in the laboratory. Afterward, the thorough anthropological examination of the bones and teeth recovered from the grave has been carried out in the field laboratory.

THE POTTERY

The pottery assemblage collected during the last two seasons (2013 and 2014) at Ghazali was abundant – to date, over a thousand diagnostic potsherds, both hand- and wheel-made, have been recorded.

The clearing of the Room 8 situated south-east of the North Church produced the greater part of the pottery fragments collected, yielding about 30% of the total amount of the pottery collected during the 2013 season. The repertoire of the vessel types was not very extensive, comprising mostly gadus, dokas, and cooking pots. Only a few fine ware pieces were recovered, including a number of inscribed ones. Some of those fragments were decorated with pained or incised decoration.

The second most numerous group of pottery sherds (about 25%) came from the clearing of the South Church unearthed in 2013. The great majority of the sherds are of the coarse ware, mainly fragments of gadus, dokas, and cooking pots.

The rest of the ceramic material came from the surface cleaning of the area directly adjacent to the south-eastern outer wall of the North Church. As the material was collected from the topmost layers its value as a dating factor is of little significance. Only one of the vessels in the pottery assemblage from the 2013 season was complete. It was a small, handmade bowl recovered in the apse of the Southern Church, used probably as a lamp.

To date, over 400 diagnostic potsherds gathered during the 2014 season have been documented. They were collected from the area directly adjoining the southeastern enclosure wall of the monastery complex. The most numerous were fragments of coarse ware, although compared to season 2013, the diagnostic pieces of fine ware represented a greater percentage. About 9% of the fragments were decorated.

The most significant find of the season was apottery deposit recovered from Room 3. The deposit comprised of 125 vessels, the great majority of coarse ware, including two completely preserved, large, ovoid beer jars. Only a few sherds were of fine ware and only one of those (a large plate with a ledged rim) has painted decoration.

Examples of the excavated pottery:

Ghazali 2014 Cemetery C2

Robert Mahler

Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw

Full version of the article in PDF

Preliminary excavations at the C2 cemetery in the immediate vicinity of the medieval monastery in Ghazali have been carried out at the beginning of 2014.

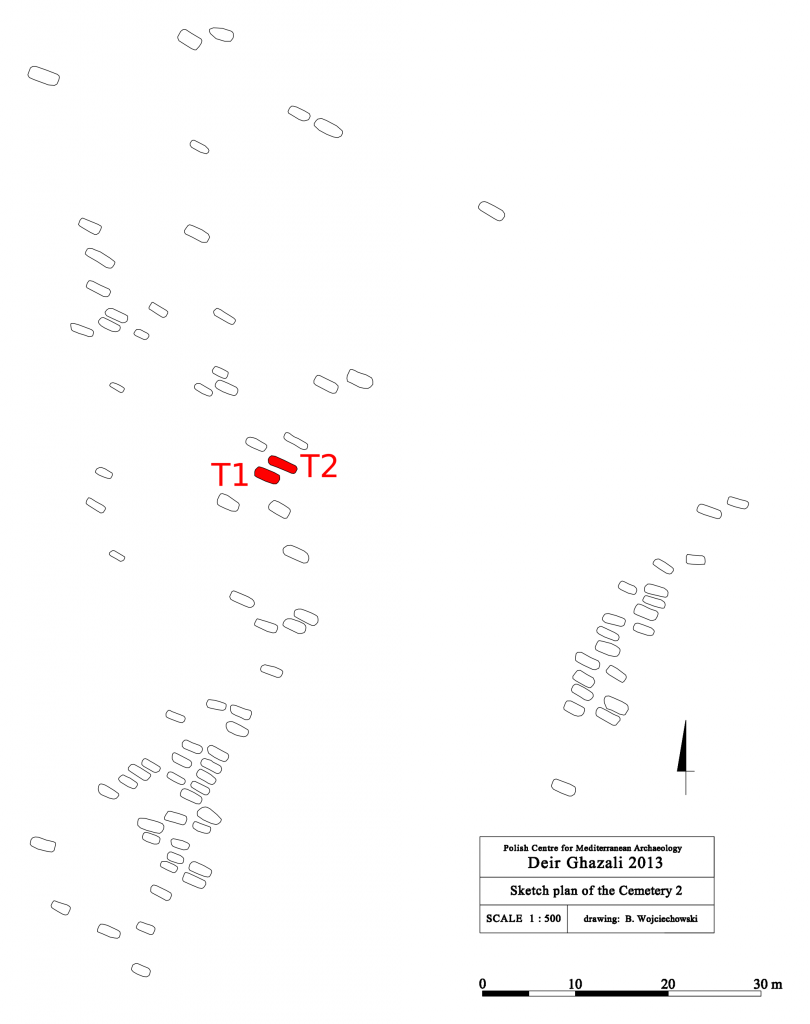

Figure 1: Initial plan of the C2 cemetery (drawing B. Wojciechowski)

Figure 2: Superstructures of graves T1 and T2. A view from the East (photo R. Mahler)

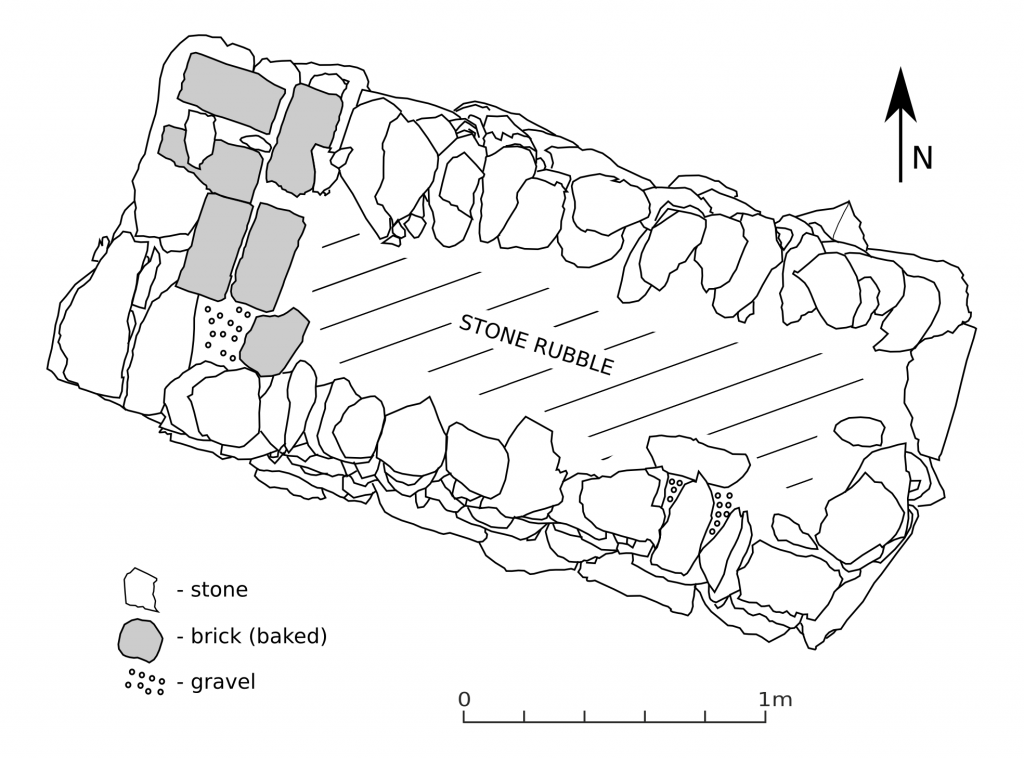

Aerial survey preceding those works allowed B. Wojciechowski to prepare an initial version of the grave inventory [Fig. 1]. Selection criteria were very strict and many structures of uncertain purpose, clearly visible on the surface were not depicted. Two of several dozens of the structures recognized as graves have been selected for excavation. Layers of soil and rubble of decayed stone covering them have been removed. It exposed the structures to the level they were originally built on [Fig. 2]. The larger superstructure (T1, older of the two – most probably) have been thoroughly documented and disassembled [Fig. 3] and the underlying grave pit have been explored.

At the very bottom of the grave pit, a skeleton of a male at the age of 50 or more has been discovered. Lying in a supine position in the more or less East-West direction, with head to the West, facing East, it was following the widely recognized pattern of an ordinary Christian burial (Welsby, 2002, 48–49). The head of the interred was protected by a head shelter of three mud bricks forming a solid roof above. Burial was undisturbed, and the skeleton was found laying in anatomical order [Fig. 4]. The moisture, fungi, insects and plant roots have damaged bones considerably [Fig. 5], leaving them very fragile and fracture prone, making their proper recovery very difficult.

The inhumation was documented in detail and excavated. As expected, no grave goods have been been found accompanying the body, save some small fragments of a shroud or clothing, heavily decayed. They have been sampled for further examinations to be carried out in the laboratory. The only sample that survived mishandling during the transportation was a very small (about 1 cm2) fragment of a textile found under the head, stuck to the occipital region of the skull of the deceased. It survived but was reduced to a small pile of dust. Unfortunately, there were no other textile fragments recovered from T1 that could be sampled instead. The sample’s poor state of preservation rendered any macroscopic analyses useless. Interestingly, a C14 analysis yielded

Figure 3: Superstructure of T1, a view from above (drawing R. Mahler)

a very early date (between IInd and IVth century AD). However, carbon to nitrogen ratio revealed in the chemical composition of the sample indicates it was contaminated with bone tissue. Regrettably, it was not even the textile specialist was able to extract pure fabrics from the pulverized sample.

The thorough anthropological examination of bones and teeth recovered from the grave has been carried out in the field laboratory. Apart from sex and age determination, given above, it allowed the intravital height of the deceased to be assessed. According to K. Pearson’s (1899) regression formulae, the deceased was 168 cm tall. Owing to his advanced age he lost nearly all his teeth and his alveolus was almost fully obliterated. All his bones were very brittle and relatively light, indicating considerable loss of compact substance. Margins of his lumbar vertebrae bodies were considerably overgrown and their surfaces were pitted suggesting intervertebral disc disease – a condition common for his age (Waldron, 2009, p. 43).

Bioarchaeological description of the only individual examined in 2014 does not give even a vague idea about the people that lived there. Hopefully, further excavations at the cemetery will render paleodemographic analyses of the medieval population of Ghazali feasible.

Figure 4: T1 grave pit with skeleton exposed (photo R. Mahler)

Figure 5: Left humerus with traces of termite(?) activity and post mortem fractures (photo R. Mahler)

References:

Giannecchini, M. & Moggi-Cecchi, J. (2008). Stature in archeological samples from central Italy: methodological issues and diachronic changes. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 135(3), 284–292.

Pearson, K. (1899). Mathematic contributions to the theory of evolution V. On the reconstruction of stature of prehistoric races. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical or Physical Character, 192, 169–244.

Raxter, M., Ruff , C., Azab, A., Erfan, M., Soliman, M., & El-Sawaf, A. (2008). Stature estimation in ancient egyptians: a new technique based on anatomical reconstruction of stature. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 136(2), 147–155.

Ruff , C. B., Holt, B. M., Niskanen, M., Sladék, V., Berner, M., Garofalo, E., …, Niinimäki, S., et al. (2012). Stature and body mass estimation from skeletal remains in the european holocene. American journal of physical anthropology, 148(4), 601–617.

Trotter, M. & Gleser, G. C. (1952). Estimation of stature from long bones of american whites and negroes. American journal of physical anthropology, 10(4), 463–514.

Trotter, M. & Gleser, G. C. (1958). A re-evaluation of estimation of stature based on measurements of stature taken during life and of long bones after death. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 16(1), 79–123.

Trotter, M. & Gleser, G. C. (1977). Corrigenda to “estimation of stature from long limb bones of american whites and negroes,” american journal physical anthropology (1952). American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 47(2), 355–356.

Waldron, T. (2009). Paleopathology. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Welsby, D. A. (2002). The medieval kingdoms of nubia: pagans, christians and muslims along the middle nile. British Museum Press.

Photos from the 2014 season: