The fourth century CE has seen the rise of three separate kingdoms in the area previously known as Meroe: Nobadia (Migi) in the north, further upriver Makuria (Dotawo), and the southernmost Alodia (Alwa). All of them converted to Christianity in the sixth century CE. Then, probably at the end of the seventh century, Nobadia and Makuria merged together to form one state entity.

The heyday of the Nubian kingdoms lasted between ca. 850 until 1050. The rise of the Ayyubids and then the Mamluks in Egypt changed the relations between Nubian kingdoms and the world of Islam. Destructive invasions of the first dynasty at the end of the twelfth century and of the latter in the thirteenth century started a period of gradual decline of Makuria.

The royal court moved probably to Nobadia (Gebel Adda?) and a petty kingdom was formed in the vicinity of Dongola, which then became liegemen of the Funj sultanate. The fall of Alwa could be probably attributed to the movement of the tribes from the Arab Peninsula in the thirteenth century.

NOBADIA

Nobadia is the northernmost of the three kingdoms. It spread from the first to the third Nile cataract in its heyday. The dawn of Nobadia dates back to the end of the fourth century.

The fall of Meroe brought to life in Lower Nubia two competing chiefdoms: Blemmyan in the Dodekaschoinos and Nobadian grouped around the second Nile cataract. Dodekaschoinos is the name of the territory immediately south of Aswan, derived from Greek Dodekas choinos which means twelve (Roman) miles, and equals 75 modern miles. In ca. 420, Olympiodorus of Thebes, a Roman historian, visited the Blemmyes. According to his account, despite controlling the Nile valley the Blemmyan king preferred to remain in the desert. At the same time the Nobades, whose royal cemeteries have been found in Qustul and Ballana, started an expansion to the north. As a result, the Nobades subdued the Dodekaschoinos and settled relations with the Byzantine Empire, which allowed for an increase in the volume of trade and an influx of new political and religious ideas.

In the middle of the fifth century, the Nobades controlled the whole territory between the first and the second Nile cataracts. Then, they directed their military expansion to the south, and in the sixth century, they held sway as far upriver as the third cataract. At the beginning of the sixth century, the Nobadian elite strengthened its position within the multiethnic society, and searched for effective forms for integration of the state and its peoples, and reached for the Christian religion. The king of Nobadia converted officially in 543. The capital of Nobadia was located at Pachoras (arab. Faras).

To read more on research in Faras go to the PCMA UW website.

ALWA

The origins and history of Alwa, the southernmost of the Byzantine Nubian kingdoms, are very poorly known. The ethnicity of the founders of the new realm is obscure, but Alwa is considered a Nubian kingdom, as it was probably created by the Black Noba. They are mentioned in the inscription of Ezana, the king of Axum, who invaded the Nile Valley in the fourth century CE. At that time they dwelled along the river Takkaze and Atbara, eastern tributaries of the Nile.

The capital city of Alwa, Soba, was excavated by Peter Shinnie and then Derek Welsby. Alwan buildings at Soba were almost completely dismantled, reportedly to build Khartoum in the 1820s. There is no other Alwan settlement ever touched by the archaeologist’s trowel and at least five huge archaeological sites await excavation along the White and Blue Niles.

According to the Arab historian Ibn Selim al Aswani, who wrote in the tenth century, it had large monasteries and rich churches. Soba must have also been an important trade center, as is confirmed by the presence of Muslim traders and archaeological finds of the twelfth- and thirteenth-century: Chinese pottery and a stone mold for casting medallions bearing an Arabic inscription.

To read on the recent research in Soba, go to the PCMA UW website.

MAKURIA

Archaeological investigations today focus on the central Nubian kingdom, Makuria. The majority of Arab historical narratives concern Muslim relations with this kingdom, yet excavations uncovered so far only about 3% of its capital, and no other settlement has been investigated by archaeologists.

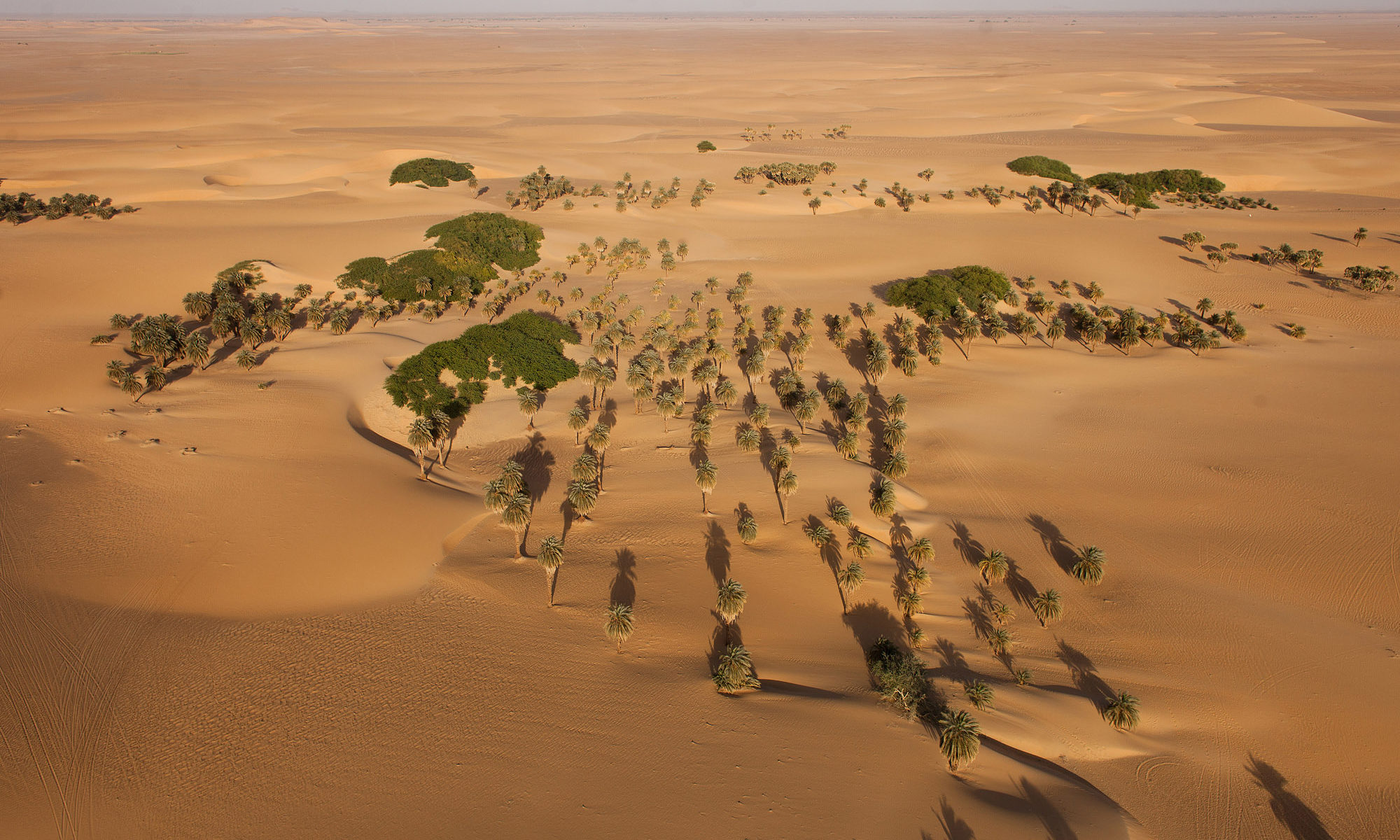

Apart from that, there are the partially excavated: monastery of Ghazali and two at Old Dongola, a pilgrimage center at Banganarti, and an enigmatic site at Hambukol. The political and social center of the kingdom was located in the area between the third and fourth Nile cataracts, a territory consisting of large Nile basins: Kerma and Letti. Dongola, the capital of the kingdom, was located in the Letti Basin, right on the spot where an extension of Wadi Howar, which connected the Nile Valley with Central and Western Africa, joins the Nile.

The beginnings of state formation in Makuria go back to the fourth decade of the fourth century and are attested in inscriptions of the Axumite king Ezana. His mighty army was held off by the Red Noba just after it had crossed Bayuda. The first center of the new political organism in the Nile valley was located near the modern villages of Zuma and Tangasi, where two vast elite cemeteries are currently under excavation by the Polish archaeologist Mahmoud el-Tayeb. The individual royal mound graves reach 50 feet in height and 200 feet in diameter.

Makuria, like its northern neighbor Nobadia, converted to Christianity sometime around the middle of the sixth century. Reportedly, the king was baptized by a mission sent by the emperor Justinian. Both kingdoms united at some point in the seventh century CE, beginning of the eighth at the latest.

In 641 and 652 the Nubians were one of the few peoples capable of repelling the Arab invasions thanks to their archery skills. The Arab historians call them “pupil smiters” or “archers of the eyes” since they were able to shoot a man through a pupil of the eye from a long distance. Both sides signed an agreement (called the baqt) that lasted for the next five hundred years regardless of who ruled Egypt. According to the treaty, the Makurians were obliged to deliver slaves in exchange for wheat, lentils, and cloth.

The king of Makuria had absolute authority. Ibn Selim Al-Aswani, an Arab historian, stated that the king had the power to turn his subjects into slaves. Several officials are attested for the Makurian kingdom. Most of them had Greek titles, e.g., eparchos, meizoteros, architriclinus, and were probably modeled on the Byzantine court. An official that played an important role in the administration was the Eparchos of Nobadia (who was kind of a viceroy of Makuria), who wielded power over the northern part of the country.

The kingdom of Makuria had a very interesting system of succession, according to which the heir was the son of the king’s sister, not the king’s own offspring. It made the king’s sister, who in Nubian textual sources holds the title Mother of the King, one of the most important and powerful persons in the realm.

To read more on research in Banganarti, Dongola, Tangasi, and Zuma, go to the PCMA UW website.